Transfer of Work

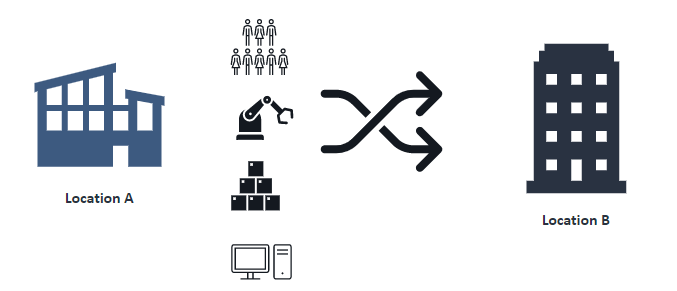

Transfer of Work, or TOW, involves the movement of all products, people, materials and associated activities from one site to another. These are often manufacturing operations but can also involve service processes. When a TOW is not properly managed it can negatively impact customer service, quality, and profitability. In our recent webinar, Fidel Kandell reveals 6 groundrules for ensuring a successful TOW. Catch the instant replay here or continue reading!

Transfers of Work can be messy. These types of projects are often complex, requiring much strategy, coordination, and excellent communication between the teams. If you are overseeing or managing this type of project, it boils down to making sure both the transferring site and receiving site are on the same team. Here are the key groundrules:

#1: Ownership. The site that is transferring its operations does not just ‘pitch’ the product over an invisible wall. They must own it until completion. As the process experts, they’ve seen it all and done it all. Now, it’s up to the receiving site to trust the experts, to ‘catch’ the product or service, and accept the challenge. One approach is to tie both sets of KPI metrics so that both sites either succeed or lose together.

Another way to control ownership is to gauge the willingness for both teams to meet all agreed timelines. This is generally done through frequent project management reviews. During one of my first TOW projects, the plant manager of the pitching site was also assigned ownership of the product’s KPIs at the catching factory. This removed any of the typical excuses for why a project was not going as planned. It also incentivized both sets of project teams to be creative and collaborate.

#2: Staffing, staffing, staffing! Use your most experienced people for such a large undertaking. NO ROOKIES! In fact, key positions at the pitching site throughout the transfer will demand full-time responsibility. Refrain from assigning your star players another side-job. Make this their one and only priority. At the catching site, there will most likely be periods with partially dedicated resources to support the transfer of work while they balance other day-to-day duties. The tipping point will be somewhere near 1/3 of the project execution after which the catching site may need to assign fully dedicated resources.

Remember that the receiving site is not familiar with the new product or service, so first-rate staffing is a must. Do not use inexperienced workers for critical leadership roles. For the TOW projects that I led, it was customary to identify key positions and request the best and brightest workers even if it meant reassigning those talented resources from other departments.

#3: Financial accountability. There are many valid reasons for relocating a partial or an entire business; supply chain consolidation, operational efficiencies, product or service synergies, to name a few. The initial work transfer project proposal should contain information that outlines potential risks and should clearly state the need for change. This typically also identifies any critical success factors which might include cost reductions, lead-time or process-time reductions, quality improvements, customer or internal operational constraints, etc. The initial business proposal should ultimately look to confirm an alignment to the business strategy or need.

A good TOW plan delivers on its financial commitments, whether it’s Contribution Margin or an overall project payback. This means that a budget with both Investment and Expense funds be established and controlled by the project manager with regular oversight from the Finance team. One way to achieve this is to adhere firmly to any headcount targets. It’s often tempting to throw more resources at the catching site if the project gets behind schedule. But doing this might mask an underlying issue rather than address the pain point. It’s best to understand the root cause. For example, is the project behind schedule because some key equipment is stuck in Customs? Adding more people will only exacerbate the cost because the machine still needs to be released, no matter how many people are added.

Another often overlooked aspect during a TOW is failing to keep close track of Plant & Equipment assets. This can have financial implications given the importance of depreciation schedules that will be transferred as information or data to the receiving site. Be sure to maintain an up-to-date inventory of the tags which can trace any of the equipment that needs to be transferred or was previously removed from the pitching site. Working closely with a Finance or Maintenance colleague will minimize errors or loss of property.

#4: Proper documentation. An absolute must is up-to-date drawings, procedures, bills of materials, routing sheets, operational instructions, service instructions, product control plans, customer information, etc. Do not underestimate the time commitment that Engineering and Information Technology teams may require to clean up the documentation. Do not wait until the end of the project to assume the IT department will dove-tail the needed data into the new site’s existing systems. This alone may add months to the project and can bust the project’s budget.

I recall one TOW that required four engineers to perform six months of work to update design changes that were still marked as “temporary” deviations on product drawings. On yet another project, I hired a full-time person just to translate work instructions into the local language.

#5: Control of the Supply Chain. Keeping detailed records of shipments and receipts seems like an obvious activity but you’d be surprised how many opportunities for error exist. This is especially true given that site operators from the pitching site are likely to be under duress, working long hours, often on weekends or off-shifts and, in many cases towards the end of a project, using skeleton crews before the shutdown. Be sure to include trusted and valued materials planning experts to keep up-to-date records of the materials coming in/out of both sites. This includes performing frequent Inventory Control audits. Measure any Finished Goods or ramp-up material plans continuously through diligent record-keeping. For service industries, keep track of any stocking or late-point identification materials which might even be located at a customer’s site.

And be sure to understand the import/export regulations. I once struggled to cross $2,000 worth of custom-made wooden pallets from the US only to be held up in border customs since they were not properly fumigated. It also turned out these could have been made locally. On another occasion, the product coming out of the new catching site in the Caribbean had significantly longer overseas transportation lead-times, which had not been properly communicated to our customers. This set off unplanned discussions for how to improve the overall logistics network after the transfer.

#6: Capability. Often, we delude ourselves into thinking our products or services are great and therefore we can transfer them “as is”. This can be disastrous because of underlying issues which might only be known to those closest to the action. There might be a piece of machinery or tool that is not working properly. Don’t transfer it! Fix it before moving it to the new site. Or perhaps one of your service technicians does not have the most recent certification to perform necessary training at the catching site. This is where a Capability Analysis of your current product and process will highlight the risks and gaps that need to be addressed. It’s important to place up-front rigor to validate your operations before any transfer even begins. Just remember that complexity is in the eyes of the catcher. One of the most successful transfers I led occurred when the pitcher assembly Line Leader volunteered to live with the catching site until the new assembly line performed to the required cycle-time. That was an extreme example of the pitcher going the extra mile to support process capability.

In summary, a TOW project is often a transformative process meant to shift operational, financial, and/or strategic plans by adapting to the new competitive business landscape. TOWs can be complex and demanding. The vital components of a TOW project require a mind-shift away from an “us versus them” mentality. Early engagement from your best workers, financial responsibility, and a clear understanding of the company’s current state and capabilities are essential to a winning strategy.